Becoming a Witness

Although Elie Wiesel (1928-2016) wrote 57 books, he is perhaps best known for his first book, “Night,” a memoir and reflection on his experiences in two Nazi concentration camps, Auschwitz and Buchenwald, in 1944-45. Wiesel is also well known for being a lifelong peace activist. He was a founding member of the Human Rights Foundation, based in New York City, and later established the Elie Wiesel Foundation to continue his work protesting oppression. For all these efforts, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. Krista Tippet, host of the NPR program “On Being,” describe Wiesel as “a towering moral figure.”

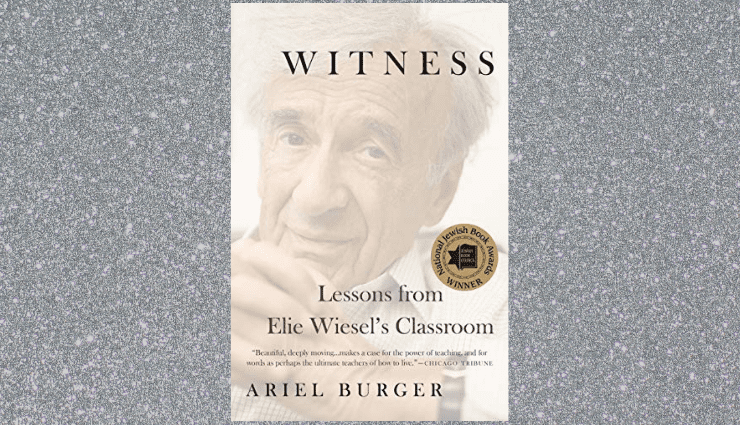

But according to Ariel Burger, author of “Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom” (Houghton Mifflin, 2018), if you asked Wiesel about his core life mission, “his answer was always the same: Teaching.” After World War II and the loss of his parents and sister in the concentration camps, Wiesel continued his studies and became a journalist. He published “Night” in 1956 and began giving lectures on classical and modern philosophy. In 1972, he was invited to teach at City College in New York. Four years later, he moved to Boston University where he taught classes for the next 34 years.

It was at Boston University that Ariel Burger met Wiesel and served for a number of years as Wiesel’s teaching assistant before setting out on his own career as a writer, teacher, artist, rabbi, and social justice worker. During his time at Boston University, Burger was so impressed with Wiesel as a teacher and human being that began taking detailed notes about his professor, who in time would become a mentor and lifelong friend. In “Witness,” Burger offers insights not only into Wiesel’s mind and work but also into what, for Wiesel, matters most in the classroom — the steady, human attentiveness that must always be front and center if we hope to heal this world.

I picked up this book because of my interest in Wiesel’s writing, but it quickly became clear that “Witness” is an excellent book for our troubled, divided times today. In the current world climate, Burger writes, “we need compelling moral voices, models of integrity, and they are hard to find.” Elie Wiesel was once such model. He believed in the power of education to change our cultural trajectory for the better. He believed that through openhearted, academically engaging discussion, we could challenge each other to write a better history of humanity — and he set out to do this one student at a time, semester after semester, for 34 years.

One of Wiesel’s signature classroom practices was to have an open question period in which students could ask any question about his life and work. In one of his Boston University classes, a student asks, “Professor, what kept you going after the Holocaust? How did you not give up?”

“Learning,” Wiesel says. Then he adds, “If there is a solution to the problems humanity faces, education must play a central role. I know that learning saved my life and I believe it can save us.”

But he also makes it clear that “learning” is not — and can never be — a matter of straight academics knowledge. “One of the darkest days of my life after the war,” he adds, “was when I discovered that many of the killers, high-ranking Nazi officials and front-line murderers alike, had advanced university degrees.”

What Wiesel offers in the name of quality education is what many independent schools, in their mission statements, say they want: smart and good graduates. He wants all of his students —all of us — to not only find our path in life but also to develop the moral backbone to stand up for human rights everywhere. One of the gifts of Burger’s book is his detailed recreation of conversations and debates in Wiesel’s classrooms. In every one, we see students and teacher wrestling with the questions that linking their studies to core issues in human society, connecting literature, religion, and philosophy with historic and contemporary events.

Through Burger’s eyes, we see Wiesel and his students examine questions of personal and collective memory. We listen to them plumb the complexities woven into our cultural, religious, and racial differences. Alongside them, we wrestle with questions of faith and doubt. We consider the role or literature and art in bringing about a more moral world. We examine the question of what it means to be a peace and social justice activist today — how to be a witness to suffering in order to end the suffering.

For teachers, there are clear lessons in how to engage students in these difficult moral conversations. There’s also an excellent reading list distilled from a number of Wiesel’s courses over the years. It’s also interesting to listen in as Burger himself wrestles with questions of his professional future — of finding one’s place in the world that is personally and professionally satisfying while also serving a greater good.

While Wiesel is reluctant to tell his students how to think, throughout the book, Burger captures a number of moments when Wiesel does speak directly to his students about what he believes matters in school and life. In one open-question session, a student asks, “What gives you hope?”

Wiesel responds: “You give me hope, your sincerity, your quest for knowledge, for meaning. When two people come together to listen, to learn from each other, there is hope. This is where humanity begins, where dignity begins, in a small gesture of respect, in listening. Hope is a gift we give to one another.”

Much thanks to Ariel Burger for keeping detailed notes in his days as a TA, for staying in contact with Wiesel throughout his life, and for translating all these experiences into a compelling book. To read “Witness” is to enter into Wiesel’s classroom as an eager student again — and to find hope for the future. In the end, Burger wrestles with the question of what it means to be a student of Wiesel’s. It’s not about living up to the great man’s reputation or achievement. As he puts it, it’s about “being yourself and cultivating your humanity, your sensitivity to others, in every moment…. It means becoming a witness.”

As Rabbi Irving Greenburg said of “Witness,” “Read this book and become a better person.”

Michael Brosnan is an independent writer and editor with a particular interest in education and social change. His latest book of poetry, “The Sovereignty of the Accidental,” was published by Harbor Mountain Press. He can be reached at michaelbrosnan54@gmail.com.