Open Spaces: Fostering Civil Discourse

This is a piece from CS&A’s winter focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion in schools. Read more from this series here.

The other day I was listening to NPR’s Morning Edition. I found their collaborative story with Sesame Workshop, “The Things Parents Don’t Talk About with Their Kids… But Should” relevant and compelling as both a parent and an educator.

The program started with a challenging question: “How do you talk to your kids about race? About ethnicity? About gender or class?” How, in other words, do we talk with children about social identities and differences, so that our children develop both a healthy sense of self and a deep understanding and respect for differences in others?

The Sesame Workshop survey made it clear that parents, in fact, rarely talk about core issues of social identity with their children. The study indicates that the lack of discussion is not due entirely to parental discomfort. Parents don’t think to directly address identity unless their children come home upset about things said to them regarding aspects of their identity.

This is a problem, of course. We know, for instance, when parents don’t talk with their children about race, children not only grow up with confused notions of race and racial identity, they also become adults who don’t know how to talk about race. Equally problematic, when it comes to fleshing out the complexities of identity with children, we tend to leave the task to parents occupying marginalized identities. Parents who identify as female and parents of non-binary children are more likely to talk about gender identity with their children. Families with members who identify as LGBTQ+ are more likely to talk about sexual orientation. Families whose religions are marginalized are more likely to talk about religious differences. While these conversations are essential for those families, the majority of children are still left to figure things out — or not — on their own.

The point of the NPR program is simply this: Children are naturally curious. When they see difference in the world, they will question it either explicitly or internally. In fact, research tells us that we start distinguishing differences as early as six months old. Without adult engagement, however, children will likely develop inaccurate and potentially harmful perspectives. Parents, therefore, need to talk with their children about difference and social identity early on — and not just in response to an issue that arises in a child’s life. When it’s a proactive process, parents can foster positive identity formation in their children and encourage a healthy respect for differences.

It is particularly beneficial for parents in dominant groups to talk with their children about identity and difference. White parents should talk about race. Heterosexual parents should talk about sexuality and non-traditional family structures. Parents of cis children should talk about gender as a spectrum rather than a binary. Addressing marginalized identities helps all children understand and support difference — and helps create well-functioning, diverse communities.

Of course, the same applies to schools.

For too long, schools, like parents, have had a tendency not to talk proactively, or in any depth, with students about matters of identity. When schools open dialogue about such issues, they tend to do so infrequently or in response to a problem or crisis.

The NPR program got me thinking again about how we can shift the paradigm in independent schools to one that normalizes regular conversations about difference year-round. How do we inspire one another to engage with and across difference as a school community? Ideally, these conversations start in the elementary years. While I certainly encourage elementary and middle schools to take on this work as a matter of best practice, because I’m the principal of a high school, I am tasked with fostering this conversation with older students.

My school, Georgetown Day School (Washington, D.C.), has a long history of engaging in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). In fact, the school was founded in 1945 to be the first racially integrated school in Washington, D.C. Today, students of color make up 40 percent of the student body. Our mission makes it clear that the school “honors the integrity and worth of each individual within a diverse school community. Georgetown Day School is dedicated to providing a supportive educational atmosphere in which teachers challenge the intellectual, creative, and physical abilities of our students and foster strength of character and concern for others.” In other words, we strive to cultivate a warm, diverse, inclusive community in which we nurture and support students to become comfortable with who they are, confident using their voices, courageous in their pursuits of excellence, and committed to leaving the world better than they found it.

Much of this work takes place in the classrooms, but it also happens through multiple forms of social engagement and school-run programs. I want to highlight one such program in particular — one I hope other schools will consider implementing. When I arrived at Georgetown Day School two years ago, I met a passionate and sophisticated group of seniors and student leaders who made a big impression on me. They shared their deep desire for the school to provide more intentional opportunities for students to engage in proactive conversations about topics relevant to their lives before the topics became hot button issues. In partnership with those students, and then Assistant Head of School for Equity and Social Impact, Crissy Cáceres, we implemented “Open Space” conversations in the high school, and we are now entering our third year of these exercises in civil discourse.

Open Space discussions are small-group, single-grade conversations led by two to three student and faculty facilitators. The facilitators receive training in facilitation but are not experts on the discussion topics. They are not meant to present or to teach but to keep the conversations safe and constructive. There is no teleological end goal to an Open Space gathering; the discussion is the beginning and end. Sometimes students arrive at an action plan, but more often than not, the period ends and we disperse to follow through in personal ways, with a deepened understanding of the issues and the perspectives of classmates. The idea is to have students speak to each other intentionally and be willing to weigh in with their thoughts as well as to pause and genuinely listen to one another. The hope is not to change others’ minds, or to reach a consensus of opinion, but to hear and see each other and to feel heard and seen. Of course, we also hope students gain greater clarity on the issues discussed and understand themselves better.

We have three Open Spaces scheduled for the 2019-20 school year and have just completed our first session focusing on the following topics: Environmental Justice, Healthy Choices (i.e., alcohol use and vaping), Political Difference, and Sexism & Sports Sports Culture. In the coming months, some of our other topics will include Mental Health, Religious Differences, Socioeconomic Status, Consent, and the intersections of these complex topics. All of these topics were identified by the student body in polls and surveys.

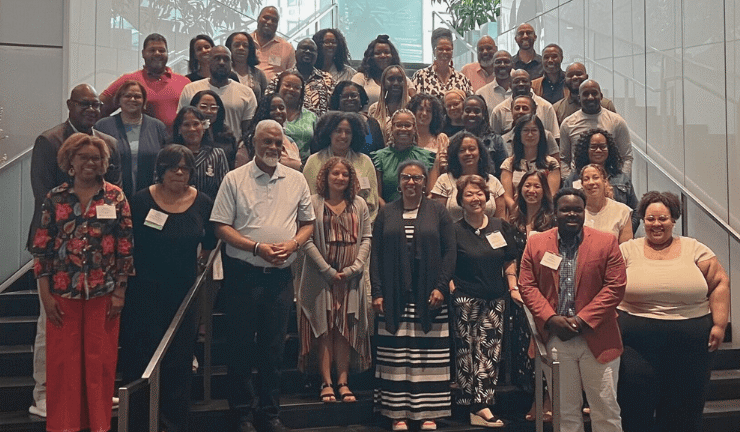

Each year we have iterated the experience to be slightly different and to cover a range of topics sometimes in mixed-grade groupings and sometimes by grade level. In our first year, we had 35 different workshops. Here is a sample that highlights the diverse range of conversations our students were leading:

- “I’ve Got 99 Problems” and the N-Word is One,”

- “Can’t You Take a Joke?: The Dangers of Normalizing Sexist Humor,”

- “(De)Centering Whiteness at GDS,”

- “Antifeminist Language: These Words Are Harmless, So What Are They Bitching About?”

- “Modern Anti-Semitism — From College Campuses to Charlottesville,”

- “The (Im)Possibility of Equity and Inclusion at a Private School,” and

- “A Non-Denominational School in a Political War-Zone.”

As we head deeper into this presidential election year, we know it’s likely to inspire heated exchange and debate about the candidates and the issues at stake. In our homes and schools, one of our goals should be to talk with young people about these issues — particularly those that intersect with identity and difference — and to find a variety of ways for them to engage across differences with more humanity.

Our Open Space meetings are one way we are practicing this skill at Georgetown Day School. We are embarking on other related initiatives to help students build these habits of open and respectful inquiry in the coming months. Our aim is to offer settings in which students can engage proactively in conversations about social matters that not only shape so much of our nation and world but also shape their lives.

I’m sure there are other ways schools can engage in this work, too. What matters most is that we take the initiative — as parents and educators — to engage children proactively in respectful dialogue about the issues that shape so much of their personal and public lives so that they feel comfortable with who they are and are empowered to shape a just, equitable, and inclusive world.

Katie Gibson is the High School Principal at Georgetown Day School (Washington, D.C.).