Best Practices in Mentorship and Leadership Development

This spring, CS&A is shining a spotlight on women in leadership. This is the final piece in a series of stories about female leaders in independent schools, the importance of mentorship, and their professional journeys. Find the full series here.

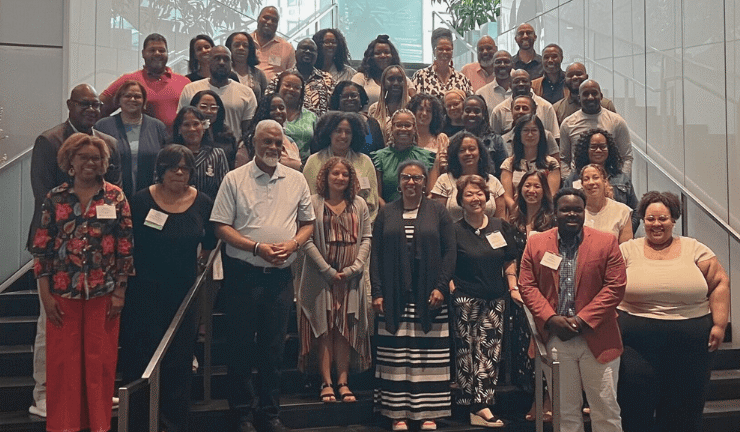

CS&A is proud to have hosted the third-annual Women’s Institute on June 14 in Boston, an event designed to support women and their allies in the education community. Our Placement and Search Groups are dedicated to increasing the number of women in leadership roles as part of our commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Nearly a decade ago, Reveta Bowers, longtime head of The Center for Early Education, in West Hollywood, California, wrote a prescient article for Independent School magazine on the importance of the independent school community consciously supporting, encouraging, and guiding the next generation of independent school leaders. In it, Bowers noted that many heads of school were aging baby boomers who would be leaving their posts soon. The financial crisis of 2007-2008 slowed the process of headship retirements somewhat, but it picked up quickly this decade.

In her article, “Developing Future Leaders: One School’s Solution (Pass It On),” Bowers writes, “I believe that one of our obligations as school leaders is to develop and nurture future generations of talented and motivated educators who are interested in school leadership.”

Then she adds: “Finding people to fill headship positions won’t be a problem; the problem will be in finding the right people.”

Finding the right people to lead schools, of course, is what we do at Carney, Sandoe & Associates. But much of the work of generating, supporting, and growing that talent lies with schools. The more schools can consciously identify and nurture talent, the deeper the talent pool will be — and the better off schools will be. In particular, given the low percentage of people of color and women in headship positions, we encourage schools to focus time and energy on developing and supporting these future leaders. Diversity research makes it clear that racial and gender equity in leadership is not only the right thing to do, it’s also the smart thing to do — for individual schools and the school community as a whole.

As Bowers puts it, “Our overarching goal should be to help develop a deep and talented pool of candidates from which our boards and search firms can draw as they seek out the next generation of administrators and leaders for their schools.”

This work includes both identifying and supporting aspiring leaders and creating school programs that encourage aspiring leaders to step up and challenge themselves.

In separate pieces, we profile four pairs of head-of-school mentors and their mentees who would go on to lead schools themselves. Here, we’re offering collective advice from these eight educational leaders on what other heads of school can do to support and nurture the next-generation of school leaders, as well as steps aspiring leaders can take to ensure they get on the leadership track.

One-on-One Mentorship

Today, school heads not only can do a great deal to support and nurture leaders within their own schools, they need to think of mentoring leadership talent as part of their on-going work. As Peter O’Neill, former longtime head of school and now senior consultant with CS&A, notes, “A core job of heads today is to help people grow and fulfill their potential.”

How can heads do this? Here’s a short list of suggestions:

- Offer aspiring leaders multiple opportunities to develop their leadership skills within your school — then offer honest feedback.

- Appoint aspiring heads to key school committees and have them serve on a variety of board committees.

- When the opportunity arises, offer them control of key short-term projects. This leadership practice helps them develop their skills and build their résumés so they can jump into first-time headship or other senior-level positions with the ability to hit the ground running.

- For all aspiring leaders, but especially for women aspiring to headship (given biases in the hiring process), make sure they develop the financial skills necessary for success — particularly regarding budgeting and fundraising.

- Help aspiring leaders understand the role of communication with constituents — how to work well with faculty, how to engage with parents, how to connect with students, and how to communicate with the outside community. The art of communicating is at the core of any head’s successful tenure. Heads need to articulate the mission, create a compelling narrative, and drive enthusiasm and support for the school’s programs and initiatives.

- Support aspiring leaders’ attendance at key conferences — and encourage them to present regularly. In this way they engage with a larger community of talented educators, develop a network, and gain greater clarity about their own philosophy of education.

- Offer them literature on school leadership that you find valuable. Discuss these books and articles with them — and how the concepts connect to the school program.

- Be a model of continuous learning. One of the quickest ways to fail as a school leader, says Barbara Chase, former head of school and CS&A senior consultant, is to think you know everything you need to know.

- Create an environment in which it’s not only safe to take risks but makes sense to take risks.

- Make it clear that aspiring leaders can propose ideas and ask you anything at any time.

- There’s an art to be the decisive leader, but research tells us that collaboration matters, too. To that end, aspiring leaders should be given opportunities to work in and lead teams when possible.

- Heads of school today need to be highly strategic. To this end, they need to dedicate time for generative thinking, to ask questions to which there is no easy or clear answer but that will lead to new and better approaches. Aspiring heads also need the opportunity to engage in this kind of generative thinking that leads to institutional change.

- Help aspiring heads develop resiliency. Even the best school leader gets hammered at some point, especially in this era of deep political and social divides. The companion to resiliency is resourcefulness, helping aspiring heads find the support they need to deal with every tough situation they face.

- For heads mentoring women leaders, it’s important to let aspiring women leaders know that they can balance family and school life. For women who are hired as new heads, Aggie Underwood adds, it’s also important to set expectations with the board. If, for instance, a new head has a young family, she needs to be clear about time needed for the family.

- Much of mentoring is about helping instill confidence in aspiring heads. Mentors of women should also alert these aspiring leaders to the likelihood of stereotype threat — that is, when people subtly raise issues of gender and competence — since it can make women less confident and less likely to seek leadership positions.

- In conversations on mentoring leaders, Ann Teaff keeps circling back to a core point: mentorship can’t be forced upon young educators. It’s important that aspiring school leaders reach out to current leaders who inspiring them, whose approach to leadership they admire. Mentors, of course, can encourage leadership engagement. Once a connection is made, the overarching goal is to give aspiring leaders opportunities and then trust them to take charge.

Some school heads are hesitant to mentor rising stars because they don’t want to lose these talented educators to other schools. While it’s true that mentoring future leaders — especially if you do it well — means you are likely to lose these leaders to other schools in time, there are many reasons to do it. For one, says Aggie Underwood, aspiring leaders, given support, serve their schools well for however many years they work there. To not mentor aspiring leaders because you don’t want to lose them, she says, is to do these leaders and your school a disservice. Aspiring leaders bring immense energy and focus to their work. While they are with you, they are a major asset to the school and help drive a culture of engagement.

In an era in which it’s nearly impossible for heads of school to manage the leadership workload alone, it also helps to have a strong team of creative, aspiring leaders who can keep your school evolving with the times.

In short, mentoring talented educators is a far better choice than trying to hold them back.

School-Based Programs

The school leaders interviewed for this piece all argue that mentoring should be an institutional practice. Every head should not only feel a responsibility to identify and support potential leaders, they need to be intentional about mentorship. To this end, it helps to include mentoring in the head’s job description. Even better, schools should include in the strategic plan the leadership’s commitment to supporting and encouraging professional growth of aspiring leaders in their community.

In her decades as a school leader, Reveta Bowers has done her part to mentor future leaders. Dozens of educators she has mentored and championed are currently leading independent schools. But she also made a point earlier in this century to establish a program in her school — the Leadership Fellows Program at The Center for Early Education — that consciously offers aspiring leaders that chance to take leadership initiatives, learn the ropes, and develop skills that will help them gain the experience and confidence to lead a school in time. Setting up a formal program is a way to ensure that educators contemplating leadership are given an opportunity to pursue their interests and build their résumés.

Another approach employed at other schools is to offer teachers the option of stepping into leadership roles on a rotating basis — say, a department chair or mid-level administrator — as a way to both learn more about leadership and get a clear sense of whether leadership advancement is what one truly wants.

The essential point is that a culture of mentorship and professional growth needs to be a stated institutional value. Schools that do this are schools that develop forward-thinking cultures that lead to some of the best cutting-edge programs. These are also the schools that attract talent.

Outside Leadership Programs

Every year, numerous independent school educators look to advance their careers through formal education programs. Schools would be wise to create a funding source for aspiring leaders to develop their skills through these programs. There are many options for education leadership in general. A core group of programs focus on independent schools in particular, including:

- Klingenstein Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College — offering a Summer Institute for Early Career Teachers, three leadership-focused master’s degree programs, and a Heads of Schools Program.

- The Independent School Teaching Residency at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education — a collaboration with two consortiums of independent schools to create outstanding teachers and education leaders.

- Independent School Leadership Program at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody School of Education — a M.Ed. program focusing on independent school leadership.

- Harvard Graduate School of Education Masters in School Leadership — a program focused broadly on school leadership, with a track specifically designed for charter schools, independent schools, and education nonprofits.

- NAIS Fellowship for Aspiring School Heads — a yearlong program involving mentorship, leadership counseling, special programming, and collaborative projects.

- State and regional association programs — many of the state and regional associations of independent schools offer excellent opportunities for educators to develop their skills as leaders.

Of course, we also encourage schools to send aspiring leaders to both the CS&A Women’s Institute (each June) and FORUM/Diversity (each January). These events are designed to help women and people from underrepresented groups valuable networks of like-minded educators and to find mentors and professional allies who can help advance their careers.

Parting Advice to Women Aspiring to Leadership

While participating in the NAIS Aspiring Heads Fellowship, Jenny Rao had a sobering insight. Most of the men in the program were in their thirties while most of the women were in their fifties. There are cultural forces at play that undercut women in leadership. Because the majority of school heads are men, younger men feel more confident in their abilities and in the likelihood of success. Women, on the other hand, carry more doubts — about their abilities, or the timing of headship, or the chances that they will get a headship appointment at all.

The overall culture needs to change. Until it does, the heads interviewed for this piece advise women who aspire to headship to have faith in their skills, ability, and training. They encourage women to reach out to leaders they admire and ask for support and opportunities to grow. This is not a time to sit back and wait to be discovered. As Jenny Rao puts it, “Headship is the most rewarding work. Trust yourself and your training. Seek out leaders who can support you. Make the leap.”

*********

Skills to Cultivate

Aspiring heads need to develop the specific knowledge and business acumen in order to run a school well. The list includes everything from fundraising and budgeting to working with the board and faculty to communicating the school’s narrative to the broader community. There are also numerous personal skills that will help ensure success. These latter skills include the ability to:

- Develop the art of deep listening

- Build and work with a leadership team, but also make decisions

- Engender trust and confidence within the community

- Be diplomatic, but also be willing to have tough, honest conversations

- Remain curious — a lifelong learner

- Keep school culture and climate at the center of the work

- Hold a 30,000-foot view of the school while developing close relations

- Learn from mistakes

- Be aware of strengths and weaknesses

- Take problems and challenges head on

- Have a sturdy ego, but be kind and humble

- Prioritize the work

- Avoid burn-out — know boundaries and develop self-care

- Have a strong moral compass — and trust it

- Ask for feedback and welcome criticisms and suggestions, as well as praise