08/18/2017 by Michael Brosnan |

The Schoolroom

What Would Ted Do?

In March 2017, the executive board of the Coalition of Essential Schools (CES), an organization of like-minded private and public schools, announced it was shutting its doors after 33 years. For many of us who found our way into the field of education through the writings, vision, and thoughtful prodding of the coalition’s founder, Ted Sizer, this announcement was a somber benchmark in American education.

In her keynote speech at the final CES conference, Nancy Faust Sizer — Ted’s wife, writing partner, and educational leader in her own right — made it clear that all reform movements run their course. The times now require younger educators to take the reins. She also made it clear that, just as Ted didn’t want to be seen as “warmed over Dewey,” future movements shouldn’t aim to be “warmed over Sizer.”

I’m among those who look forward to what the younger generation of education reformers bring to the table — especially since the field has gotten more complicated by the damaging entanglement of politics and corporate interests. Still, it hurts to see this particular movement in education reform relegated to the sidelines. The schools themselves and a loose association through the coalition website, now run by the Francis W. Parker Essential Charter School, will continue. But the central organization that ran an annual conference, among other things, is finished. So, before we move on, I would like to say something about why Ted Sizer and the Coalition of Essential Schools have mattered over the past 33 years — and what we need to carry forward.

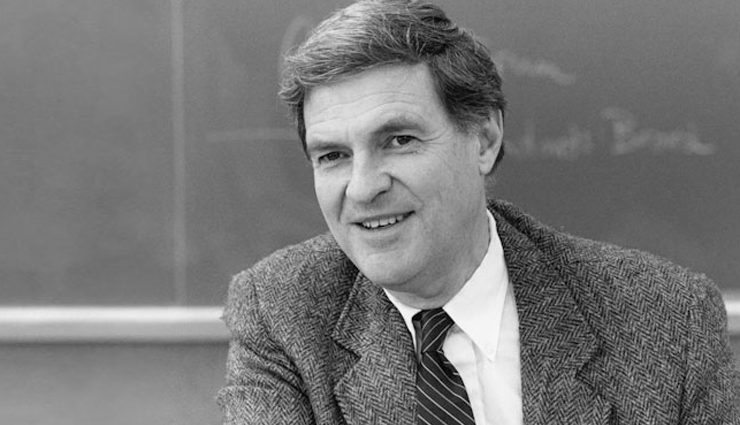

Sizer, for those who aren’t familiar with him, was a central figure in the conversation on American education reform from the late 1970s until his death in 2009. He served on faculties at Harvard and Brown and as the president of Phillips Academy in Massachusetts. He wrote numerous influential books on education, including “Horace’s Compromise” — a reform-minded investigation that grew out of a 10-year study on American high school education. In 1984, as noted, Sizer founded CES — a coalition of public and private schools that adhere to shared practices and principles. Starting in 1993, he also served as the founding director of the Annenberg Center for School Reform based at Brown University. After retiring from Brown, he took a one-year position as co-principal (with Nancy) of Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School, which gave the Sizers the opportunity to put principles into practice. Afterward, Sizer returned to the Harvard Graduate School of Education where he taught a course on redesigning the American high school.

I first met Sizer in 1996, when he agreed to write a blurb for my book, “Against the Current: How One School Struggled and Succeeded with At-Risk Kids” (Heinemann, 1997). But I got to know him better when working as his editor on a few articles for Independent School magazine — including one co-written with Nancy, titled “The Students Are Watching,” which went on to be among the most read articles in the magazine and the foundation of a book on the same topic.

When I think of Sizer’s work, I think primarily of his wish to always humanize education — to remember that each child and teacher matters and that schools are, first and foremost, humane communities. At the start of “The Students Are Watching,” the Sizers underscore this view: “All of us still struggle to be ‘civilized,’ and we need institutions which will nurture our humanity…. In the end, we teachers and other adults who care about children should attend to even the humblest of these actions and dangers, so that we may teach our students — and ourselves — a worthy way of life.”

In American education, the simple clarity of “a worthy way of life” as the focal point of education should be obvious, but it always seems to run into the buzz saw of special interests. The result, as the Sizers put is, is that “Americans have burdened themselves, however unintentionally, with a high school design that is inefficient and runs counter to an abundance of solid research about how formal learning in fact takes place.”

Ted Sizer’s argument for rethinking high school essentially boils down to this: The federal government should offer guidelines and standards, but those standards should be carried out locally as states and local communities see fit. The government oversight, as with hospitals, is to ensure that schools are basically going in the right direction. Sizer wants a “largely local, messy, independent movement [that] lessens the likelihood of a stifling and politicized national system that rams a particular brand of ideas, those expressing a single ideology, down the throats of individual families and communities.”

Although Sizer cared deeply about our traditional public school system, he embraced a broad spectrum of schools, including independent charter schools and traditional independent schools. Among the schools committed to the CES principles are a number of independent schools, including the Atrium School in Massachusetts, Eagle Rock School in Colorado, and the McDonogh School in Maryland.

His notion for essential schools is born of the belief that, with guiding principles, independence, and proper funding, public and private schools can serve their communities well. Those essential principles boil down to following:

- Schools should focus on helping students learn to use their minds well.

- It’s better for schools to aim for depth of knowledge rather than breadth. Less is more.

- School goals should apply to all students. To the degree possible, the curriculum should be customized to meet students where they are and to adapt to the students’ way of learning.

- Students should be viewed as workers; teachers as coaches.

- Students should be able to demonstrate mastery. Teaching and learning should be documented and assessed based on student performance of real tasks — not on time spent in school.

- Schools should “explicitly and self-consciously stress values of unanxious expectation, of trust, and of decency (fairness, generosity and tolerance).”

- The faculty should be committed to the entire school. It’s great to be an expert in a subject area, but a teacher’s obligation needs to be as a generalist committed to the health of the school community.

- Resources should be dedicated to teaching and learning — to providing students and teachers with what they need. This includes time for teacher collective planning and support for ongoing professional development.

- Schools should be committed to democratic principles within the school community and both honor diversity and build on its strengths.

I can think of non-CES schools that embrace many of these elements — though few embrace them all. Some of these principles, such as the demonstration of mastery, stubbornly remain on the fringes of the conversation on school reform (see The Mastery Transcript Consortium). The concept of teachers as coaches — a concept supported by brain science — is too often dominated by the notion of teachers as deliverers of instructional material. We may know that helping students learn how to learn is better than “covering” a wide range of information; we just can’t seem to break free of the latter practice.

I also know of very few schools that stress values of “unanxious expectations.” When I mentioned this latter principle to a teacher at an independent school with a great reputation, he just sighed, “Wouldn’t that be wonderful.” In too many independent schools, the level of student anxiety over high achievement runs counter to the stated missions of those schools. Part of the problem, I think, comes with how we view the term “rigorous” and think about “competition.”

In “The New American High School,” the book Sizer was working on at the time of his death, he digs into some of these principles in detail. When I first read the book, I was struck by how practical it all sounds. But in time, I’ve come to see how his vision is primarily a humane one. I suppose the genius of the CES is this balance of the practical and the humane.

In the book’s “Differences” section, Sizer sums up the reason why we need to differentiate our teaching as much as possible:

Just as we teachers come to recognize the value in our students’ different opinions, we must also be ready to teach them in a variety of ways. If, in the style of John Dewey, the child is truly to be at the center of her own education, we must be prepared to address her in several fashions: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, but even more. We must know whether a slower or quicker pace, a brisk or loving style, a competitive or collaborative model, will lead to the best outcomes for each particular activity. Even if we decide that a particular child learns best by hearing things, we must be prepared to explain those things in several ways, as many as it takes…. It may take longer, but schools are not assembly lines because children are not widgets.

The whole Differences section, in fact, is a great reminder for teachers about why we need to keep CES in mind as we move forward. The CES asks us to pay deep attention to our students — who they are, what motivates them, how they see themselves, etc. Each student matters — and we need to acknowledge and act on it as best we can in schools. We need to focus on that place where “community and individuality can coexist.”

In the chapter on “Courses” (his preferred term for what we teach), Sizer outlines the qualities we should aim to instill in students. The list includes the skills of listening, self-expression, empathy, restraint, responsible autonomy, the habit of attending to the legitimate needs of others, and the habit of wonderment.

These skills are all important — and I love that he highlights them while leaving the question of course content to educators — but the last one strikes me as the most overlooked of all. Sizer writes: “The habit of wonderment [is] the practice of the creatively wandering mind. Such minds have produced most of our culture’s new knowledge. What if I look at this matter in a new way? a scholar of any age might ask. The habit of creative and informed wonderment should be an objective of any course.”

What I love about Sizer’s writing is his consistency over the years. He not only appraises education honestly and thoughtfully, he has always kept the teacher and student at the center.

Sizer saw the messiness of education, the constant evolution, the space for debate. For him, it is never easy or formulaic. There are no Seven Steps to Better Teaching or Four Secrets of Great Schools. Rather, he asks us to think carefully about everything, stay awake to shifting needs, be alert always to the actual children in our schools and classes. He asks us to consider the language we use to talk about school — especially the core words that comprise the foundations of our beliefs about school and learning.

As Sizer saw it, it all boils down to purpose: “We want our students to grow up to be informed, principled, and free.”

Let’s carry that message on.

Michael Brosnan is an independent writer and editor with a particular interest in education and social change. He can be reached at michaelbrosnan5476@gmail.com.

Leave a Comment

0 Comments

There are no comments on this blog entry.